Stability, Maneuverability and Controllability

Part 2

By Greg Gremminger

We will explore the differences between Stability, Maneuverability and Controllability. These are the sources of some misunderstanding. They are not the same things and they are not necessarily directly related or mutually exclusive. The differences are both interesting and important to our appreciation of our own abilities and proficiency levels in the machine we are to fly today.

First, for the purposes of this article, some discussion of terminology:

✓Stability: The ability of the gyro/pilot system to return to steady flight after a disturbance from steady flight. An unstable machine (gyro/pilot system), once disturbed from steady flight, will continue in an oscillatory motion or even diverge into worsening oscillations. Stability of aircraft is often assessed in both stick free and stick fixed conditions as how quickly the machine returns to steady flight after a disturbance. However, the pilot control responses (on the stick) are often the predominant factor in the stability of the overall gyro/pilot system due to the fact that the pilot control input may stabilize or actually destabilize the system - depending on pilot proficiency in that particular machine and environment. The resultant stability of the gyro/pilot system is mostly achieved by stable control of the rotor disk, as that lifting surface is the means by which flight path is maintained or changed.

✓Airframe Stability: This is distinct from the overall gyro/pilot stability. The airframe is that portion of the gyro, which hangs below the roll and pitch gimbals of the rotorhead. The gyro airframe is basically a pendulum that may swing or deflect relative to the rotor disk. That pendulum may be excited into a swing or deflection by the lift or accelerations of the rotor or by the actions of the pilot. The airframe maybe separately stabilized to the airstream, or it may be allowed to free swing relative to the airstream and the rotor disk. As discussed below, the airframe is not necessarily directly linked to or affecting the rotor disk. The airframe movements or swinging may not appreciably affect the flight path of the machine unless those movements cause cyclic inputs to the rotor either directly or through pilot response on the stick.

✓Maneuverability: The overall agility of the aircraft, or the physical ability of the rotor disk to affect a maneuver in flight path or attitude of the whole machine (yaw is separately controlled by the rudder and is not addressed in this discussion). Some of the factors affecting the agility of a gyro to make a maneuver are; rotor blade inertia, size, etc., and the overall weight of the machine.

✓Controllability: The ability for the pilot to initiate and control a maneuver’s speed and precision by controlling the rotor disk through the gyro’s cyclic control system. Factors affecting controllability and that will be discussed below include airframe stability; control leverage, friction and slack; and pilot feedback sensations. Ideally, the machine’s controllability would allow the pilot to exercise that machine’s full maneuverability precisely.

Fixed wings & Rotors are different

Contrary to common or intuitive perception, controllability and stability of a gyro are not mutually exclusive features, and they are not even necessarily strongly related to the maneuverability (agility) of the gyro. It has been a common misunderstanding that a stable gyro necessarily means that it is not as controllable or maneuverable. This misunderstanding arises from the analogy with fixed wing aircraft. It is well appreciated that the more agile (maneuverable) fixed wing designs are considered to be less stable – i.e. a Pitts Special or F16 fighter! This analogy is not at all valid for most rotorcraft because the “wing” of a rotorcraft (rotor disk) is not “fixed” to the airframe of the aircraft. The rotor disk, and therefore the flight path of the whole machine, is mostly independent of the gyro airframe except for any (commanded or uncommanded) cyclic inputs through the rotorhead.

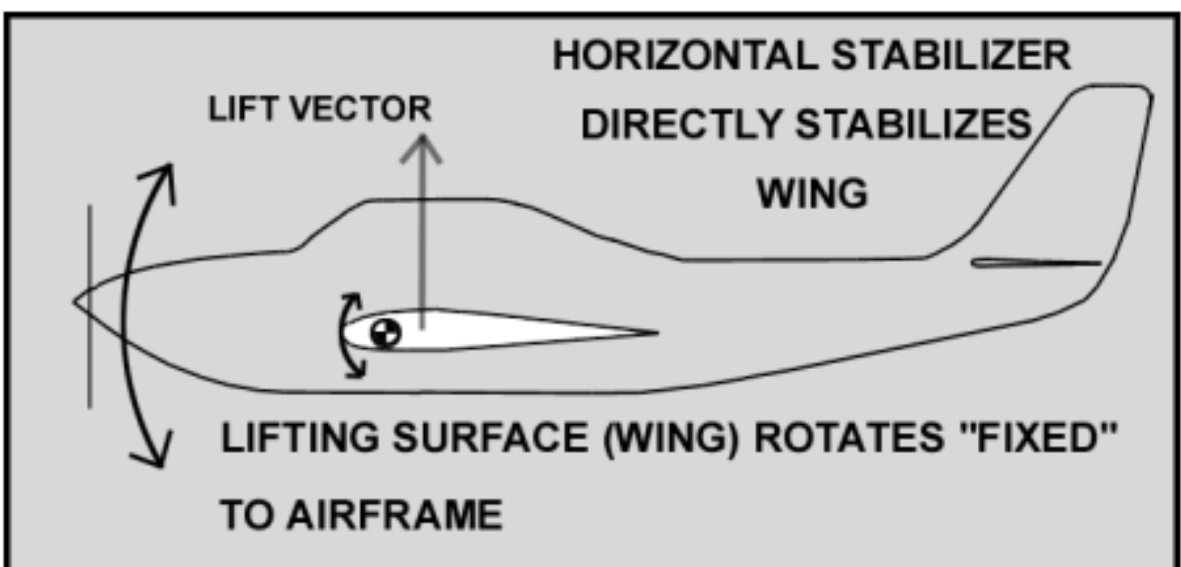

The rotor disk in a rotorcraft and the wing in an airplane are the lifting surfaces that sustain and control the flight path of the aircraft, and are the means by which the pilot controls the aircraft flight path. Effectively, the roll and pitch attitudes of these lifting surfaces control the flight path. In the fixed wing case, the attitude of the wing is exactly the same as the attitude of the airframe AND the attitude the pilot senses in that airframe. The wing is “fixed”! The flight path of the whole aircraft is directly related to the attitude of the airframe (and the pilot).

The maneuverability of a fixed wing IS therefore limited by the stability of the airframe. In most fixed wing aircraft, the airframe is stabilized via the balance of the stabilizers, propeller thrustline and center of gravity. Because the wings are fixed, the stabilized airframe directly stabilizes the lifting surfaces (wings) and thereby the also limits manueverability.

In the rotorcraft or gyro case (or in the case of a Trike or Flying Flea Flicker!), the airframe is allowed to pivot or move relative to the lifting surface (rotor disk), and does not necessarily cause the rotor disk to change its attitude or flight path. The flight path of the whole gyro is not necessarily directly related to the airframe attitude. Conversely, the ability of the rotor to maneuver the whole machine is not limited by the stability of the airframe because the rotor (lifting surface) is free to pitch and roll independent of the airframe.

In this lies the crux of the whole PIO argument between stabilized airframes and not! And this is rather interesting, because as we shall see, in the end a really important factor is the training, proficiency and pilot technique in each particular machine! But, as we will also see, pilot proficiency is most urgently a factor in machines whose airframe is not stable!

A gyro airframe allowed to swing or deflect relative to the rotor disk - not stabilized by a horizontal stabilizer or other means - will induce cyclic control inputs into the rotor disk (which may induce uncommanded flight path changes!) If cyclic control inputs were not induced into the rotor disk, the rotor and whole machine would go on, undisturbed along its current flight path. However, cyclic control inputs from a swing or deflection are, or may be, induced into the rotor by several means:

1) Friction in the control linkage or rotorhead pivots prevents the rotorhead from freely following the rotor disk. If friction forces the rotorhead to pivot with the airframe, a cyclic command is input into the rotor disk causing it to react to an airframe swing. This is called an Uncommanded cyclic input because the pilot did not intend it! (Pilot cyclic controls should always be as friction and resistance free as possible to avoid this situation)

2) The pilot holding the stick and restricting its free movement. Same thing happens as in (1) above. Depending on how tightly the pilot restricts the free movement of the stick and rotorhead, the more uncommanded cyclic input is provided to the rotor by an airframe swing.

3) The pilot, reacting to the misleading sensations of a swinging airframe, inputs corrective (commanded) cyclic inputs through stick pressures or movements. This is the crux of Pilot Induced Oscillations (PIO). Those commanded control inputs, falsely prescribed by the pilot sensing movement of the airframe, may often be unnecessary and/or out of time or in the wrong direction! This may result in a divergent or increasing set of swings and flight path oscillations as each successive swing is wrongly compensated by the pilot’s reaction.

4) By design, the Bensen offset gimbal and trim spring cause the rotor to pitch in a self-correcting direction from a sudden change in lift. This is good! However, the same mechanism forces the rotorhead to somewhat follow any airframe swing - not so good, and must be compensated by pilot technique!

5) A reverse twist on (1), (2) and (4) above is that a vertical gust will cause the rotor disk to pitch up (or down), and depending on the control system friction or the pilot’s firm grip on the stick re- stricting free movement, allow the rotor to excite a swing in the airframe - while defeating the self-correcting action of the offset gimbal. An unstabilized airframe will likely lag and overshoot, such that any swings, through continued uncommanded cyclic coupling, may diverge further without proficient corrective action by the pilot.

Most of these airframe swing cyclic inputs are obviously undesirable. They input a cyclic control that upsets the flight path and most likely induces a further swing that can lead to a divergent reaction of the gyro or the gyro/pilot system. It requires proficient and precise control input from the pilot to interfere with this divergent instability. An obvious solution to this situation might be to stabilize or reduce the swing of the airframe. This is often accomplished through an adequate horizontal stabilizer, however other factors such as airframe and rotor moment of inertia or weight may also somewhat temper the ability to excite airframe swings.

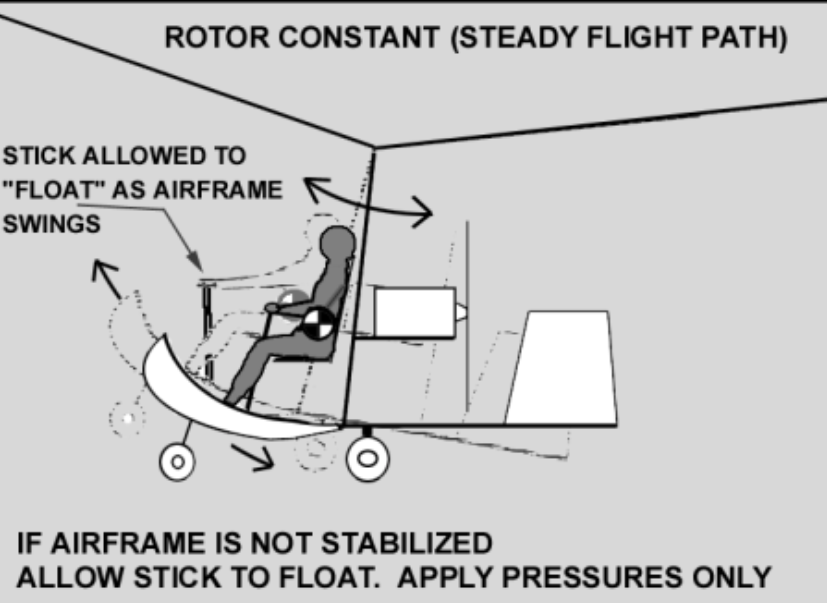

However, even on gyros where the airframe is not stabilized and is able to swing or deflect readily, good pilot proficiency through training and experience may overcome the inherent instabilities. Most of the undesirable coupling from airframe into the rotor system occurs because of pilot stick control inputs - either not allowing the stick to move or inputting improper stick movements or pressures. If the pilot allows the stick to move freely as the airframe swings, there is little undesirable cyclic input into the rotor disk. That means that the pilot should apply only force pressures on the stick, not stick restriction or movements. Only the pressure on the stick should be applied to provide commanded cyclic control input to the rotor.

Aha! This is the way we are instructed to fly any aircraft anyway, but it is especially important on a rotorcraft because of the high control power of the cyclic system. How often do you hear an instructor say to “just apply stick pressures”, “loosen up, don’t hold the stick so tight”? In effect, hold the stick loosely, allow it to float where it wants to go, urge it to go where you want it to go by applying pressure only! In this way most destabilizing swings will not couple into the rotor and will not divert the flight path from what the pilot intends! Aha, this is one way to avoid PIO, this works in most gyros whether the airframe is stabilized and can or can’t swing, and is the sign of a proficient and well-practiced pilot. Some experienced pilots actually like the control feel of an unstabilized airframe, wrongly interpreting this as a higher degree of maneuverability. Actually the machine is just as maneuverable as if the airframe were stabilized, and that pilot has mastered the jabs and timing and touch to accurately control that gyro anyway. However this is not easily mastered by the novice and may not be the same on a differently configured gyro or in different power/airspeed conditions!

Please note that this takes finely tuned unconscious automatic pilot control reactions, and that this is accomplished only through good training and frequent practice. However we don’t often get a lot of practice at the extremes of our personal envelope. Please note that extremes in the flight environment, such as high or low power, high or low speed, or extreme turbulence may dramatically affect the stability of the air- frame and therefore require different pilot reactions to properly and accurately control even a familiar machine in that unfamiliar environment. Many of our latest tragedies are the result of inadequate pilot proficiency in environments or machines that the pilot was not adequately prepared or proficient in.

We have just discussed the difference between a fixed wing and a pendulum configured non-fixed rotor/gyro system. We have seen how this can lead to gyro/ pilot instabilities. There are other factors that can affect the instability of a gyro. These other factors will be discussed in depth later, but several are mentioned here in order to appreciate that this is not a simple issue and that many other factors, other than horizontal stabilizers, contribute to the overall stability of a gyro: Rotorblade diameter, mass, weight, rpm, torsional stiffness, airfoil, reflex, etc. Propeller Thrustline, Center of Gravity (CG), Center of Drag (CD), moment of inertia, weight, fuselage shape, airspeed, etc. are also very important factors because they additionally determine the DYNAMIC STABILITY of the airframe. What is most important to understand is that these are very complex and interrelated factors, that the gyro you are flying today may have unforeseen and unexpected reactions in unpracticed areas of your personal envelope. Understand also, that a “stable” gyro is not assured by simply moving a thrustline here or placing a horizontal stabilizer there. The true stability of a gyro is a melded harmony of all these many factors and is achieved only by a thorough and involved design and testing program. If the machine you are flying does not exactly match the configuration of a well tested and proven machine, do not push the conservative limits of your personal envelope in that machine.

As stated above, a maneuverable or agile gyro is one whose rotor is capable of performing the desired maneuvers. An agile gyro may be considered such whether its agility is intentionally controlled by the pilot or is unintentionally initiated by uncommanded inputs or in- stabilities. In most cases it is desirable to have a highly maneuverable gyro. With good controllability and airframe stability, we can maneuver that gyro precisely through tight turns and quick flight path changes. A maneuverable gyro maybe highly stable or highly unstable. A maneuverable gyro is generally light and short so that inertias are not hard to overcome. A highly unstable AND highly maneuverable gyro may be more prone to Power Pitch Over (PPO) because it can so quickly pivot in the pitch axis - high pilot skills are required to fly such a machine safely. Generally a poorly maneuverable machine may be considered more stable simply because it will not make any changes quickly. But maneuverability is only related to rotor and airframe inertias, not to the stability of the gyro or airframe, or to the pilot’s ability to control that rotor.

A gyro’s controllability is also not necessarily related to its stability or its maneuverability. Controllability is the ease or ability provided to the pilot to precisely and quickly utilize the full maneuverability of the machine. Inherent instabilities of the gyro can be overcome by a proficient pilot, but generally, the pilot’s workload is reduced with a more stable machine - especially if the airframe is stable where airframe attitude and movements closely relate only to the flight path of the whole machine. A stable airframe provides a solid platform from which the pilot may precisely reference stick control inputs. The stability of the airframe may not necessarily relate to the stability of the whole gyro/pilot system, but the stability of the airframe may dramatically alter the controllability and pilot proficiency requirements to maintain or restore stable control of that machine.

Aside from a stable airframe for accurate and predictable control inputs, control linkage arrangements and irregularities may have serious impacts on the controllability of the gyro, or at least on the proficiency of the pilot to accurately control the gyro. It was mentioned above that high friction in the control linkage could input uncommanded cyclic actions to the rotor disk. The pilot will have to counteract or compensate any of these uncommanded inputs. But also, excessive slack or looseness in the control linkage introduces a “discontinuity” in the control loop, something that again requires pilot compensation and can easily lead to overcontrol. The control ratio (or leverage) of the control linkage also changes the amplitude or degree of responses required by the pilot. This is essentially like changing the “gain” of an element in the control “loop”. In Controls Engineering, the “gain” of elements within control loops are carefully managed to avoid instabilities – such as the squeal of a sound system with volume turned up too loud! A change in “gain” within the control “loop” of the gyro may require some fine tuning by the pilot especially in more sensitive environments such as at higher airspeeds.

Control power, or the sensitivity of the rotor disk to cyclic control inputs can vary from machine to machine, but especially from rotor system to rotor system. This can be an especially surprising and unfamiliar controllability factor when switching to an unfamiliar machine. Contributing factors such as airfoil design, teeter heights, blade sizes and weights, and control ratios will be discussed in more detail in later installments. This is essentially another change in “gain” within the gyro control “loop”.

A pilot’s senses or feedback from the airframe are an important factor in gyro controllability, at least from the pilot’s standpoint. The pilot of any aircraft utilizes all of his/her senses as feedback to initiate a control correction or input. Sight, seat of the pants feel, wind in the face or around a windshield, sound of the wind and the engine, are all feedback systems the pilot learns to unconsciously sense and react to. This is essentially the “feedback” that closes the gyro/pilot control “loop” from which the pilot (consciously or unconsciously) initiates his/ her control response – which may or may not serve to stabilize or unstabilize the whole system. We already mentioned the misleading sensations arising from a swing in the airframe. The additional point to remember here is that whenever any of these feedback sensations are altered or missing, you may not provide proper reactions or even stable control inputs until you learn new unconscious reactions with these altered sensations. You may not feel that wind slipping in around one side of the windscreen or sense a change in the wind if the doors are on. You might not sense the attitude or varying altitude if you are at a high altitude, over water or in poor visibility. In some machines with less stable air- frames, your sensation of airframe attitude may not reflect the rotor disk attitude or actual flight path. Be aware that when your environment changes, your envelope limits may also have changed!

In summary, the point of all these discussions is only to heighten our awareness that our proficiency requirements may change dramatically with different machines and flight environments. By better appreciating the complexities involved, and that we probably don’t know how we or our machine will react in unfamiliar situations, perhaps we will approach those situations with more caution and attention and avoid exceeding our own personal flight safety envelope.

It is my personal belief that any one of us may learn to fly any machine safely in any reasonable conditions; but that we must take the time to understand and approach our personal envelopes carefully and attentively to reach a safe level of proficiency. It is not enough to say, “I can fly a gyro.” It is essential that we also realize we may only be proficient in THIS gyro in THESE conditions. And realize that becoming safely proficient in another gyro or another set of conditions - perhaps completely different control responses required - means enough practice or repetition to burn new synapses in our brain so that our reactions are in harmony with THAT machine’s requirements in that environment.