Rotors Instead of Wings

By Greg Gremminger

When I first got into gyrocopters, I had been flying fixed-wing airplanes and ultralights for many years. What attracted me to gyros was how well they handled in the wind. Steph and I had loved flying our little Quicksilver ultralights, and especially our 2-place Kolb Twinstar. But, we were often frustrated by the uncomfortable mid-day turbulence, prompting us to voluntarily limit our flying to just a few hours in the mornings and evenings on most days.

We flew our gyro for several years before I came to appreciate the full advantages of rotors over wings in the type of flying we loved to do. I’m writing this article because I suspect that many Rotorcraft readers, especially those who may be new to the sport or newly attracted to these interesting machines, are pondering the same question – “Why should I choose rotors over wings?”

Does the type of flying you enjoy include the thrilling sensations of low level speed and height, sightseeing the terrain, and enough utility to make moderate range cross-country, “touring” flights. If you are like me, you reserve your flying for the “nice” days and wish every day was “nice” because you fly for the pure enjoyment of flight. This is basically the attraction of light and ultralight-type aircraft of all types. If your primary use of aircraft requires the utility of efficient travel or bad weather capability, or you have to fly when you really don’t want to, you should probably stick with full size, general aviation aircraft.

I learned this when I realized that most of my early years of flying general aviation planes were spent doing touch and goes in the pattern. When I started flying ultralights, I realized that what I really enjoyed was the freedom and sensations of height, speed and maneuver. Flying in the pattern kept me closer to the ground where the human brain better senses height and speed. In a “real” aircraft, except in the traffic pattern, low-level thrills tend to be discouraged. In ultralights and gyros, low level, fast or slow, turning and swooping, climbing and diving are what it’s all about – for me!

I can get what I want out of flying in ultralight-type fixed wings, but gyros let me do it more and better! Here’s why, and a lot more on the advantages I have come to appreciate with rotors.

Rotors are much less susceptible to wind turbulence:

Turbulence capability of a light gyro has been likened to flying a much heavier fixed wing such as a Cherokee 6. There are several factors involved here.

1. Rotors have high “wing loading”: The rotor blade has a much smaller area and a much higher relative airspeed than a wing. As a result, the sensitivity to turbulence feels more like you are hanging on a very long bungee cord.

2. Spinning rotors have a large amount of rotational inertia: This essentially makes it a lot like a gyroscope and resistant to upsetting the plane of rotation. In a light fixed-wing aircraft, it is most disturbing when a wind gust picks up one wing suddenly and forcefully, requiring pilot control input to bring the wing back down – only to find that the control authority of the aileron is slow to do so! This really sucks close to the ground! In a properly designed rotorcraft, it is rare that the pilot even consciously has to correct an uncommanded roll. The more noticeable effect of strong wind gusts is the vertical, bungee-like up/down movement and some tail or yaw wiggle from side gusts.

3. Rotors have a much higher degree of control authority: The cyclic control on a rotor system actually only changes the pitch of each individual blade. The control input is not really trying to man-handle the disk to a new disk angle like an asymmetrical vertical wind gust would be trying to do. The control force (required from the pilot) to change the blade pitch angle is very slight – the blades then do the tough work of changing the disk angle through blade lift. Due to the very high relative airspeed over each blade, the resulting force and effect on the rotor disk is extremely effective at actually changing the disk angle (and the desired flight path). This means that the pilot has much higher control authority with which to counter any small un-commanded effect of the wind. In fact, generally, just holding on to the stick in turbulence will usually overcome most wind roll inputs. In pitch, high control authority readily allows quick compensation for the bungee-like vertical wind effect – even close to the ground!

Before I leave the subject of susceptibility to wind turbulence, it must be understood that the high pitch axis control authority in combination with high turbulence can be the major contributing factor to PIO (Pilot Induced Oscillations) in a gyro. A gyro must be designed to automatically pitch into a vertical wind gust to avoid possible pilot induced divergent oscillations as the pilot may over-react to compensate. In other words, the nose of the gyro should pitch up when encountering a downward vertical wind gust. This is analogous to the required reaction in a fixed-wing aircraft. In addition to the standard “offset gimbal,” this usually requires the correct alignment of the prop thrust line and use of a properly sized horizontal stabilizer.

Rotorcraft can fly slow (relative to a comparable fixed-wing)

Of course helicopters can hover, but even gyrocopters can fly much slower below their optimum speed, or “behind the power curve,” than most fixed wing aircraft. A normal fixed wing will “stall” at speeds much below its best angle of attack speed. Autorotating rotors, by their nature, do not stall in the conventional sense, and are perfectly happy spinning away in even a straight vertical descent. The amount of engine thrust available will determine the slowest airspeed at which a gyro may hold level altitude. A gyrocopter, with its autorotating “wing,” may fly, fully controlled, well below the “power curve” and even at zero airspeed – however, it will be descending. The major safety factor here is that it will not suddenly pitch over as a fixed wing aircraft does when it “stalls”. (This does not mean you might not hit the ground hard if you get too far behind the power curve with neither adequate engine nor altitude to stop rapid descent!)

Rotors store and transfer energy

This is the factor that is most intriguing to me! Rotors provide a third energy storage medium. Fixed-wing aircraft store energy (from the engine) in two forms – momentum and height. Fixed-wings can exchange this stored energy between forward speed and altitude. Rotorcraft, and especially autorotating rotorcraft (gyros usually!) can additionally store and exchange energy in the rotational speed of the rotor. This provides unique capabilities such as nearly zero speed landings. In such a “dead-stop” landing, the pilot can build up and store extra rotor energy (RPM) in a steep and fast dive to the ground. The extra energy is immediately available upon flare or short hover near the ground to bring the machine to a near stop. An obvious advantage of this is the ability to use much smaller and shorter emergency landing fields.

Another fascinating application of rotor energy storage is the capability of some autogyros to “jump” into the air. Gyroplanes such as Dick DeGraw’s GyRhino, the CarterCopter, and the Air & Space 18A employ collective pitch control to spend excess rotor energy (rotor RPM) to jump into the air and transition into forward flight.

Rotorcraft can land at VERY slow forward speeds

This is the result of the rotor energy storage discussed above. Rotorcraft can “fly on” with normal forward speed like a fixed wing, or a rotorcraft can make a “dead stop,” or near hover, slow speed landing (a helicopter can actually momentarily hover as it uses up all its stored rotor energy by adding collective pitch as the rotor slows down.) The “dead-stop” or emergency-type landing is much different than a “fly-on” landing. The “fly-on” landing does not use any stored rotor energy (excess RPM) to slow the aircraft. A “fly-on” landing is the only type landing a fixed-wing can make – it has no rotor! A “dead stop” rotorcraft landing employs a much steeper, higher airspeed approach (to store rotor energy), followed by a well-timed flare very close to the ground. The superior control authority of the rotor in this rapid flare completely stops the vertical descent and slows the rotorcraft to near walking speeds just before touchdown. In fact, the rotor actually converts a lot of the forward speed energy into even more rotor energy for the final touchdown.

On an extremely rough field, the aircraft can be completely stopped just above the ground and allowed to “plop” vertically the last few inches! (I have had 3 “dead stick” landings in rough plowed fields without incident!) The same technique is used to land in high grass or crops. Try rough plowed fields or crops in a fixed wing – I’ll bet you tumble or wipe the landing gear out at best! (Been there too!) At any rate, on any landing, it’s extremely comfortable to be at slower speeds that generally won’t hurt you if something did happen.

Large L/D range (or high range of glide ratios)

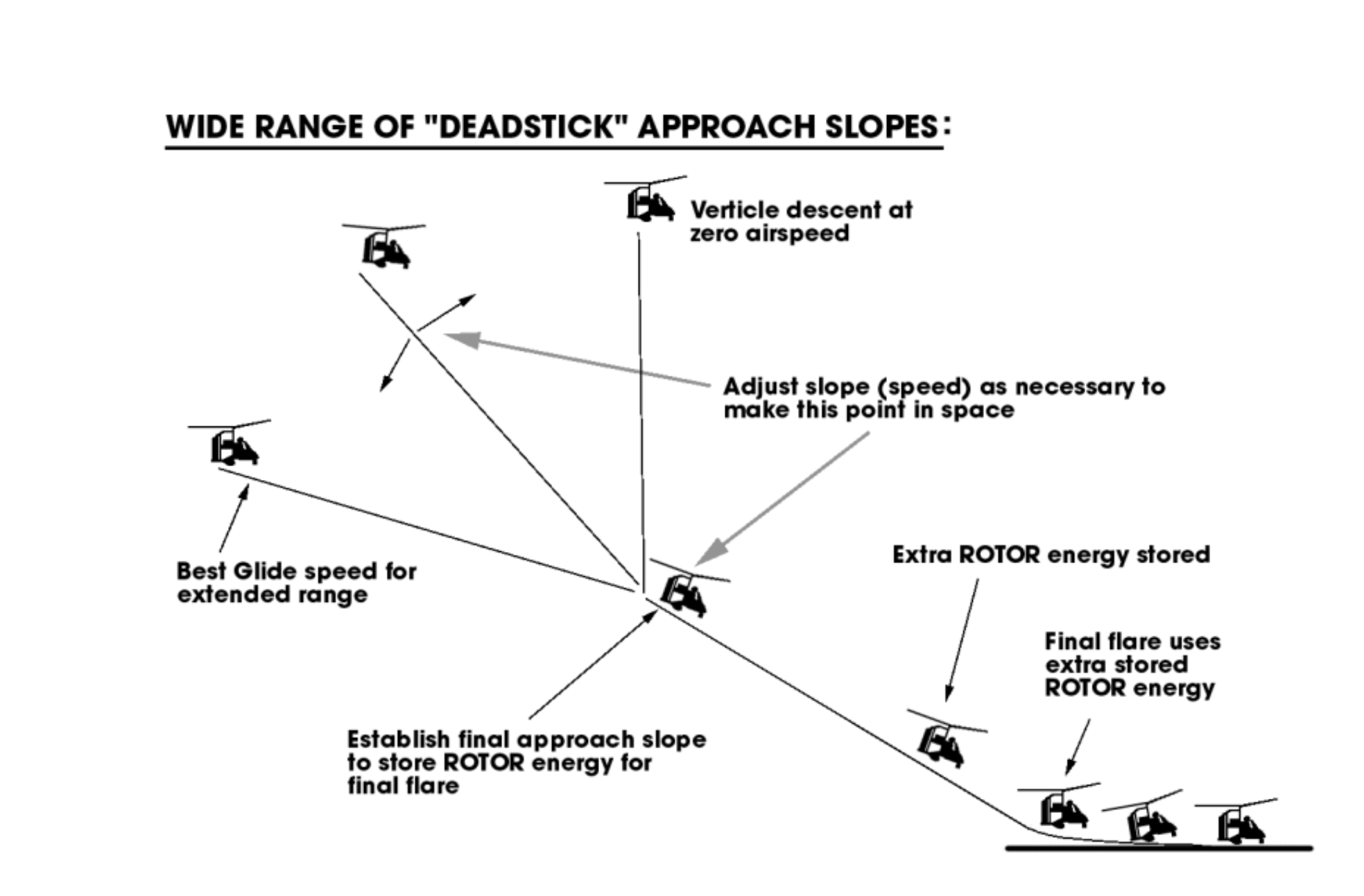

Because rotorcraft can fly very comfortably and controllably well “below the power curve,” there are a lot of approach-slope options to “hit the spot” on the ground or during an emergency landing. Fixed wing aircraft use a variety of means to control the glide, such as flaps, spoilers, slipping and sliding, and even slow flight “below the power curve.” But, at some not-so-slow speed, a fixed wing will stall and the glide-slope cannot easily be steepened much below 60 degrees without an all-out dive! Although a rotorcraft will not usually have the gliding range (shallow glide to reach a distant large field) of a fixed-wing, the rotorcraft can much more accurately and continuously adjust its glide-slope, down to pure vertical if necessary, to land in that spot below you. You don’t have to judge the descent while curving around and flying a pattern! Combined with a rotorcraft’s ability to land in a much smaller area, there are a lot more emergency landing options available– including very rough plowed fields that would normally topple a fixed wing aircraft on landing.

Additionally, an experienced pilot may continuously and easily adjust the glide-slope (descent rate and angle) throughout the glide by simply flying further or less “behind the curve.” Normal technique would be to select the point on the glide-slope where you will need to recover air- speed to make a normal “dead stop” landing, then adjust your glide-slope to get to that spot in the air. This point might typically be 100 – 200 ft altitude at a 45-60 degree slope to the touchdown point. At that point, your touchdown is assured and you execute a normal “dead stop” landing. (Pick up speed to store rotor energy for the final “dead stop” touchdown) This descent, with a fully controllable and adjustable glide-slope between about a 60-degree glide down to pure vertical is, to Steph and me, one of the most gratifying feelings of flying a gyrocopter! They are fun to practice all day long, and they really pay off in the event of a real emergency landing!

Rotorcraft store more easily in a hangar (at least the 2-blade type does)

Rotorcraft trailer more easily (most rotors come off easily for transport)

There are certainly some counter arguments that could be made in favor of fixed-wing aircraft. They may be easier to learn to fly. There are more of them around (at this time!). They are more efficient – shallower maximum glide-slope. I could just as easily write an article pro-wing. I like anything that flies! But, when I add them all up, my choice overall is our little gyro. And, if you ask Steph - past Editor – she’ll just tell you she gets more flying time and is more comfortable in more wind in the gyro. And boy does she like those vertical descents!